It seems like it was just yesterday, and yet four whole years have gone by… I figure it’s better late than never to write down the experiences and lessons learned from my time as a novice monk in Myanmar. After all, if not now: when?

In a sense, the core tenets of Buddhism and its fundamental meditative practices might sooner be seen as secular philosophies rather than “religion”. Buddhism’s aim is simple: to solve the problem of suffering. Why do we suffer, and how can we stop? I’m fairly certain we would all like to live a better life, whatever that might mean for our particular situation. For this reason, I do believe that cultivating certain qualities of mind and character through meditation is of benefit to everyone. To me, things like loving-kindness, mindfulness, and concentration are the meta-skills that can build up all of our other endeavours and lead us to a better place. But, is meditation more than just a self-help tool?

Maybe, like me, you’ve been sitting for a while and are wondering what it’d be like to dedicate yourself fully to the practice – or at least take it up a notch. What follows is my account of the year 2020, in the hopes of inspiring, helping, or at least somehow relating this journey to your own experience. I’m certainly no expert, as the following paragraphs will show. But I definitely went out of my comfort zone, and it’s a story worth telling.

I had been meditating relatively consistently since the summer of 2017 – which had marked the beginning of my Quarter-Life-Crisis™. Gradually learning, reading, and practicing more and more, I had developed a growing interest and involvement with westernized Buddhism, as presented in books such as ‘Mindfulness in Plain English‘ and ‘Wherever You Go, There You Are‘. You’ll find mindfulness meditation guides in just about every therapist’s arsenal, and with the encouragement of a new friend who swore by it, I dove into it butt-first. Eventually, by 2019, I was attending weekly meetups, traveling to multiple day- or week-long retreats, and most importantly: feeling quite different from when I had set out on this path. By the time I was done with business school, I was pretty convinced that there was something to this whole meditation thing – but what about Buddhism itself? Where did these teachings come from, and how did the source material differ from what I’d learned?

Upon graduation, I was saddled with the nauseating uncertainty that only a newly-minted MBA without a clear career path can know. Sure, I’d cobbled together some intentions, general directions, and ‘things to dedicate myself to‘, but when the rubber hit the road, I basically froze. After graduating in December 2019, I took a very long road trip to decompress and debrief – to both enjoy and reflect on my station in life. It was clear that I still had a lot of internal work to do, and I felt extremely under-qualified and under-prepared to leap in the direction I had been planning – psychedelic psychotherapy and facilitating retreats. So, I carefully considered what skills or experience would give me the confidence I so desperately lacked. Aside from networking and relationships, my mind inevitably gravitated towards the transformative power of meditation.

Part of me was admittedly after some sort of ‘peak experience’: of confirmation that Buddhist wisdom was not just words, but an experientially verifiable psycho-spiritual reality. The slow progress I’d been making wasn’t enough – I wanted the answers, now! I also wanted a way to bring myself into the flow state reliably, and without external requirements like psychedelic substances. Armed with awakening, I reasoned I’d then be ready to help others overcome their suffering. Simple!

So, I kicked into research mode and began looking into long-term meditation options. My searching eventually led me to Southeast Asia, the birthplace of the Buddha and home to the oldest, most conservative strain of Buddhism: Theravāda. It depends who you ask, but it’s arguably the most ‘authentic’ version of the Buddha’s teachings as passed down over two millennia. Specifically, I found Myanmar to be very suitable for this project: an infinitely-renewable religious visa and respected meditation centers such as Pa-Auk Forest Monastery made it my choice of destination. So, I bought a one-way ticket to Yangon for February 28, 2020, applied for a religious visa as a Canadian citizen, and made the necessary mental and practical preparations for departure. I wasn’t sure if I’d stay for a few day, weeks, months, years, or my entire life… but I was ready for the adventure. Little did I know what was brewing in Wuhan, China at the time…

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

Robert Frost

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

And so, I arrived in Myanmar on February 27th. The open road beckoned. Exciting sights lay waiting at every turn off the beaten path, silently promising to steep visitors in centuries of culture – magnificent temples juxtaposed by modern urban developments. Aromas of tantalizing foodstuffs wafted through the air, the shopkeepers and stall owners stoking their coals, keeping their frying pans piping hot, always at the ready with a morsel to offer those who passed by. The cacophony was at once discordant, yet harmonious; heavy diesel motors balanced out by the cutting jeers of youth. Locals either giggled or gasped to one another, pointing out the “for-ay-nah” who dared visit at such a precarious time in world history. On this road was the freedom to steer one’s senses wherever one saw fit, in a country that had just barely begun to embrace democracy. The possibilities were seemingly endless.

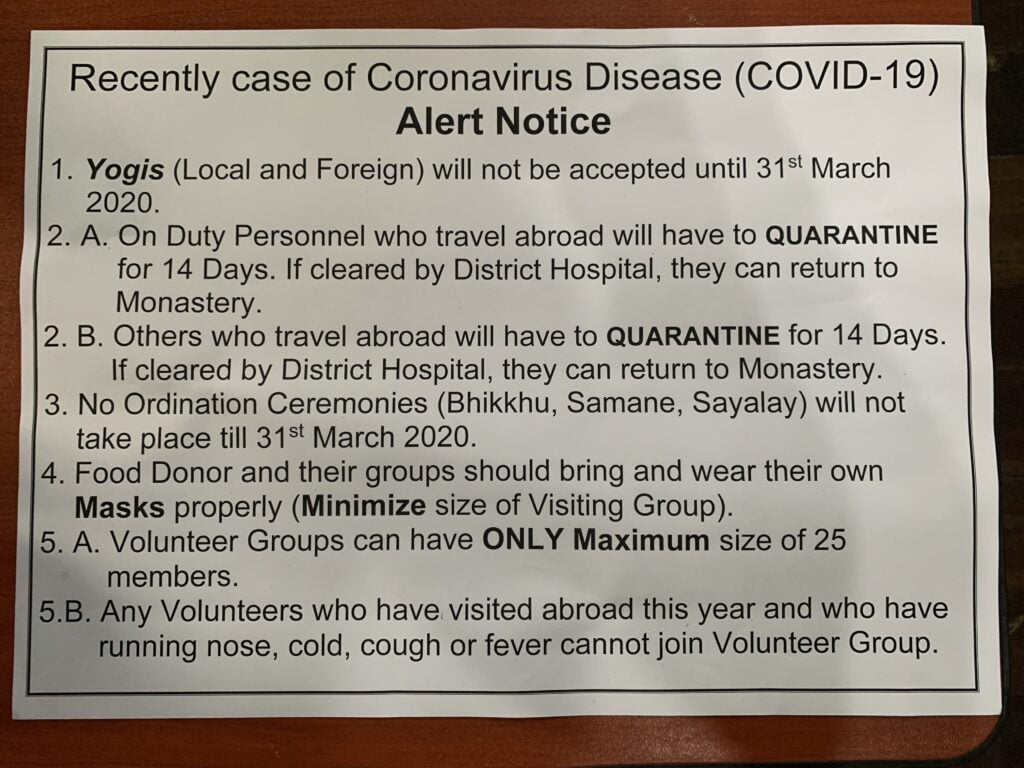

I had arrived amidst news of the first reported cases and deaths from the novel coronavirus in the U.S. Undeterred, I promptly made my way to the Pa Auk Forest Monastery, who had agreed to sponsor my religious visa. After a long and bumpy overnight bus ride from Yangon to the south of Mawlamyine, I arrived at the retreat center at around 5am. After waiting for the center to open, I made my way over to the admissions office. Unfortunately for me, I was greeted by some unexpected news:

The monk in charge of admissions informed me that I would be unable to stay at the center, due to a recent lockdown policy implemented to help protect the mostly elderly community. Having arrived on an empty stomach, he made the kind and generous gesture of sharing some of his breakfast with me. Once fed, I made my way back to the main road leading out of the center and towards the city. I sat on the side of that road for quite some time. A feeling of emptiness and longing gradually filled my chest, threatening to devour me from inside out. What was there to devour, anyway? Thirteen-thousand kilometres from home, I was more than lost. Now what?

With the help of a street vendor (and a lot of Google Translate), I managed to find a ticket for another bus heading north to Yangon. Once checked into a hostel, I spent hours searching for solutions, calling every meditation center within reasonable distance, sending messages and trying to find a place that was both open and English-speaking – a combination that proved very difficult to locate. By a stroke of luck (or perhaps karma?) I noticed a tear-off flyer on the hostel noticeboard where I’d moved to. The flyer advertised a meditation center, and stated the center is always open, always welcoming volunteers. A quick message via WhatsApp, and I received a reply stating I’m more than welcome there. Bingo.

After asking a few people about the center, it seemed like more of a WorkAway/volunteering-oriented place, but what other options did I have? I wasn’t afraid of rolling up my sleeves for a while, at least until the lockdown at Pa Auk was over. I gathered all my things and hopped on a city bus towards the outskirts of Yangon, into a town named Thanlyin.

And so, on March 3rd, I found myself taking refuge at a Buddhist-run shelter for the homeless and destitute: Thabarwa

I was greeted by a permanently-curious-looking dog with eyebrows – I’m not sure who was the more surprised between us:

At Thabarwa, the reigning element was chaos. Thousands of people were crammed into a few square kilometers, and the compound’s housing stock was not exactly built to code. Still, the residents made do, and the team of international volunteers, of which I was now a proud (if mildly disoriented) member, did their best to keep the wheels greased and the systems running: helping with patient care, washing and clothing the disabled, collecting, preparing, and cooking food, cleaning house, teaching English, and simply entertaining the residents were just some of the activities available to choose from. We were quickly warned of burnout and compassion fatigue by some of the longer-term volunteers – it was important to recharge and take care of ourselves first and foremost.

I was relieved to have something to do. I made a commitment to try a little bit of everything: today, hospital duty. Tomorrow, patient washing. Next: alms round. And so on. The sense of duty and service was a good feeling, and yet I was amazed at how quickly the environment wore me down, just as the others had warned. I had also been attending regular group meditation sessions, even attended a short meditation and fasting retreat, yet my mind was as panicked and disoriented as ever. Sure, the global uncertainty and stressful work were factors, but shouldn’t I be able to deal with this by now?

It is here that a small battle between brevity and authenticity must be fought: as mentioned above with such a chaotic environment, every day brought with it unique challenges and rare occurrences; here I could go on for pages, potentially at the expense of your patience and/or interest. After all, this article is meant to be about amateur monasticism (…or is it?) Suffice it to say, that whether it was the wildly divergent social dynamics between volunteers (exemplified by some choosing to have sex in the monastery dorms) or the openly alcoholic foul-mouthed travelers who disparaged the local religion and culture (but were more than happy to take refuge in their space), it was far from your typical volunteer gig, let alone monastery.

Still, I felt there was a lesson here, and carried on. There was a sense of community that kept us afloat – I certainly wasn’t the only one in this situation. Meditators and volunteers from all over the world found themselves essentially stuck here, especially those from hard-hit countries like Italy, Germany, and France. Flights home were all but nonexistent, and the few that remained were astronomically expensive. I figured now was not the time to turn around and run home – and go back to what? Using a sort of sunk-cost reasoning, I concluded that I had come all this way and made all this effort, and the situation back in Canada was, in a way, no better. Here, at least I still had a sense of freedom. There was no national lockdown, and COVID hadn’t really taken root (yet). So, I stayed, absorbed myself in the work, and did whatever I could to try and grasp the… unique… meditation teachings on offer.

After about three weeks, though, I sensed a growing feeling of un-ease in me – old habits and patterns were re-emerging in an attempt to numb and push away the stress. Within me, there seemed to be an internal tension that reflected the outside situation at Thabarwa: some were more interested in trying to develop and train their minds; others, more into partying and drinking their nights away. Work hard, play hard. This dichotomy also played itself out in me, as I weaved across the line between good-boy-meditator and momentary-pleasure-seeker. Unsure of where I fit in, unclear on what my goals were, and just plain overwhelmed, I decided to leave the center for a while, and do a bit of sightseeing in the north of the country. I set my sights northward, to the ancient ruins and thousands of temples littering Bagan. It was a welcome breath of fresh air to be once again journeying solo.

On arrival, the nascent pandemic was already showing its effects, by way of once-busy streets and hostels now being empty and dormant. I still met and connected with some fellow travellers along the way: the Chilean woman whose lifelong dream of traveling the world had come to an abrupt halt; the French girl on a gap year like no other; the German man who didn’t want to go home, either. In the meantime, I’d somehow taken up smoking; at 20 cents a pack, it was a cheap ticket to instant gratification. The blueish smoke from my cigarette billowed gently up towards the sky, spiralling and shape-shifting in a never-ending quest for ascension. Groundless. Formless. And as above, so below. Just as the smoke lacked a solid core, so, I felt, did I. However, a question still remained: Why had I come here? Not for this.

Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water. Now you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. […]

-Bruce Lee

Be water, my friend.

After a week on the road, I returned to Thabarwa, feeling in some abstract sense that it was where I should be. The temples could wait: a thousand years and more hadn’t erased them. The chance to transform myself, however, was a limited-time offer.

On my return, I made an effort to attend more meetings and talks. As one evening grew nearer, the time came for a weekly meeting between us volunteers and the administration. We sat on thin woven mats around a large golden Buddha-image, his half-smiling expression unchanged by the suffocating humidity – and an inexhaustible supply of mosquitoes. It was difficult to concentrate. Talks of an impending countrywide lockdown led to discussions on how to best protect ourselves against this novel virus. In such a crowded environment, where social distancing was next to impossible, we would have to make do with plenty of meditation and a healthy diet. I glanced up at the Buddha’s cryptic expression, and asked myself: “What’s your secret?”

Then came time for a question-and-answer session.

In that moment, the events of those past weeks all seemed to come together. It was now, or never. Fear engulfed my body. My mind started careening dangerously off course. Although my heart was racing with the urgency of a shock patient, I was able to touch a seed of mindfulness. Slowly, I returned focus to my breath. I acknowledged the existence of an aspiration that I somehow still hadn’t let die.

I raised my hand. The head monk (Sayadaw) motioned for me to speak.

“…is it possible to go for ordination here?”

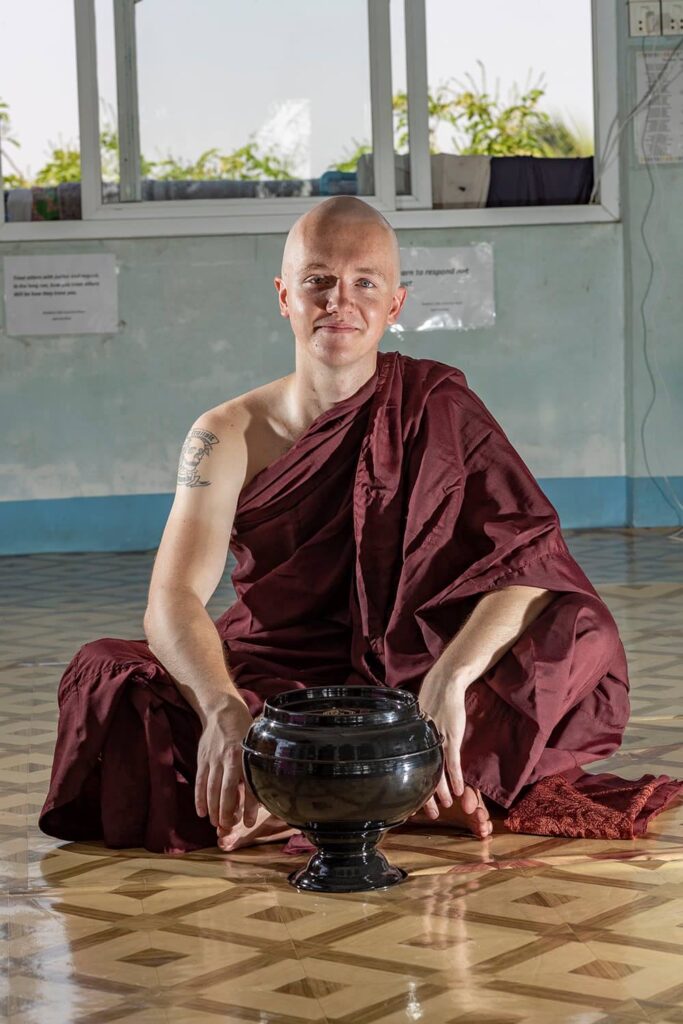

I would try to find my freedom on the path of discipline. The next day, a senior monk shaved my head, provided me with the requisite equipment, and the center organized a short ceremony. I recited the ordination rites for a novice practitioner: taking refuge in the Triple Gem, and undertaking the Ten Training Precepts. I emerged as a newly ordained novice monk, or sāmaṇera in Pali:

With a newly bald head, alms bowl, and robes generously donated by the laity, I was thrust shiny pate-first into an entirely new way of being and acting. To reinforce this transition, as is tradition, the abbott of the monastery also gave me a new name during the ceremony: Ashin Vijjācāra, which when broken down means:

vijjā, ‘(higher) knowledge’, gnosis

cāra, doing, behaviour, action, process

vijjācāra = one who is in the process or journey of obtaining deeper knowledge and insight.

I had, of course, done a rudimentary amount of research on what it meant to be a Buddhist monk. Living the experience proved to be a whole ‘nother ballgame. I instantly felt I was being held to a higher standard in every way, which seems obvious enough. This went beyond a logical or theoretical commitment, and was something I could physically feel. I became minutely aware of how I was moving, due largely in part to the completely new arrangement of clothing I bore on my body. A fellow novice from the Ukraine counselled me on the importance of etiquette: since there is no visible difference between a novice and senior monk, he recommended I keep in mind the further 75 sekhiya rules.

In reality, it is both easier and harder than one might think to uphold the ten precepts as a monk when already in a monastery, considering the monastery’s entire structure is predicated on facilitating the cultivation of spiritual qualities:

- I undertake to abstain from harming or taking life

- This is taken to include all living beings: which means the real challenge is to forego the swatting of any and all bugs and mosquitoes – of which there were innumerably many.

- I undertake to abstain from taking what is not given

- Everything that is needed to live and practice (in the form of food, materials, and shelter) is freely given by outside donation.

- I undertake to abstain from any sexual contact

- This of course includes “being your own best friend” – and this desirous energy would prove difficult to tame, as I’ll go into later.

- I undertake to abstain from false speech

- I am rather introverted by nature, and was never placed into any ethical dilemmas during my time, which made it easy to speak openly, plainly, and mindfully when needed.

- I undertake to abstain from the use of intoxicants

- I gave up the aforementioned cigarettes prior to ordination, and did not crave alcohol or other drugs. I later heard an interesting story about a sister center affiliated with Thabarwa, dedicated to helping alcoholics recover: some found that taking monastic vows helped turn their lives around completely, while others would still relapse occasionally, but far less often, providing them with a vastly improved quality of life and causing less damage to society and others in the interim. An interesting compromise between the stringency of monasticism and of doing charitable good.

- I undertake to abstain from taking food after midday

- Having experimented with fasting prior to this whole adventure, I found this way of eating very suitable, but not without its challenges due to the methods by which food is obtained. I’ll expand on it below.

- I undertake to abstain from dancing, singing, music or any kind of entertainment

- I never felt the urge to burst into song and dance during my stay. Access to the Internet and social media causes the greatest challenge with this precept. Examining the way in which one uses media and entertainment (mostly to fill time or feel a vicarious sense of accomplishment and/or excitement) proved very freeing. I became extremely comfortable with simply sitting idly and observing my internal and external landscapes, absorbing myself in tasks rather than distracting myself, and greatly reduced the time spent on my phone (which I still had access to.) That being said, some monasteries are stricter than others, and Thabarwa was certainly a place where expectations were a little lower.

- I undertake to abstain from the use of garlands, perfumes, unguents and adornments

- With nobody to impress, the simple matter of keeping clean meant using unscented soap when bathing, which I was perfectly fine with.

- I undertake to abstain from using luxurious seats

- This extends to bedding, as well. Our accommodations were humble and simple: depending on the room, either a low wooden bed-frame and/or just a thin foam sleeping pad, along with some much-needed mosquito netting.

- I undertake to abstain from accepting and holding gold and silver (money)

- This proved to be one of the most initially impactful, difficult, yet freeing efforts I undertook. I’ll explain:

Money itself, of course, is not evil, but the love of money is called the root of all evil. As Bikkhu Pesala writes, “The story illustrating the laying down of the rule shows how the first monk to accept money was overwhelmed by greed. When a certain monk was invited for alms to a house, the donor was unable to buy any meat to offer to him. The monk, overwhelmed by greed for meat, said, “Never mind, give me the money, and I will find meat myself.” So the Buddha made the rule prohibiting the acceptance of money.” As written in the Saṁyutta Nikāya: “For anyone for whom the five strings of sensuality are allowable, money is allowable. That you can unequivocally recognize as not the quality of a contemplative, not the quality of a Sakyan son.”

Money is simply too flexible a tool, too conducive to fulfilling one’s wants and desires, when the objective is to do quite the opposite: learn to be equanimous and non-attached to particular outcomes or objects. Abandoning money altogether is quite the leap, and again, only made possible by the generosity and dedication of the numerous volunteers and laypeople who give of their time and resources to support monastic life. Even then, there are still numerous modern-day monks who accept money, and this is the rule, rather than the exception in certain regions of Asia (Myanmar included). As I wanted to live as authentically as I could given the conditions, I undertook to not use or touch money at all – including transfers to/from my remaining accounts back in Canada.

This endeavour ties into the precept to abstain from taking food after midday – due to the way in which food is procured. You see, at any monastery of sufficient size, there will be an existing system of collecting, cooking, and serving food – done almost entirely by caretakers and volunteers. However, the original tradition set forth by the historical Buddha was that of individual alms collection – essentially traveling door-to-door and receiving whatever food (if any) the residents chose to give at that time. At Thabarwa (and basically all other monasteries), this had become systematized: groups of around ten monks (sometimes far more) would be dispatched to surrounding areas, walking in single file to collect a spoonful of rice each, or perhaps a snack/instant coffee packet, etc. You can view a video of the process here.

The monks would then return to Thabarwa, and empty their vessels into a communal rice store for later distribution at mealtime. To keep things clean, laypeople generally donated raw meat and vegetables directly to the center, which would then get cooked and served. The system worked well and food was plentiful – however, after participating in it for around a month, I sensed a feeling of disconnection. As with most any system or routine, the practice had become depersonalized for the sake of efficiency. The Ukrainian novice felt the same – he had come from a much smaller and secluded monastery, where he needed to subsist entirely on his bowl alone, without relying on what amounted to a daily buffet. On his advice, I undertook to attempt the same: go out for alms on my own, and eat whatever came my way. Without money, this meant total reliance on the fruits of the alms round.

This challenge yielded some of the most salient, memorable, and powerful moments in my early practice. I mentally disconnected from the safety net provided by the daily meal service: my stomach was at the mercy of the villagers. Since I was not part of a regular group, there was no longer a set expectation in terms of exact time and place for the villagers to stand, waiting to donate food. Logically, I could reason that I was nowhere near a risk of starvation – but the mind has a way of blowing circumstances out of proportion. I certainly felt totally and completely vulnerable as I walked out of our dwelling, shortly after daybreak. I stood at the head of a local residential road, collecting my attention and calling to mind the training rules: I was to walk in front of each home, stand for a short while in silence, and move along if nobody took notice. If they did, I was to receive almsfood appreciatively, in silence and without eye contact, with attention focussed on the bowl. Repeat as needed until food is at most level with the edge – though the size of the bowl makes this a huge amount of food, needed only if also feeding a sick/injured fellow monk.

The first four or five houses yielded no result, which stirred the primal, anxious uncertainty within me.

That is, until the next house, where the householder noticed me while cleaning the yard, and immediately understood that I was on my alms rounds. He quickly hurried inside, and emerged with his wife, who carried a bowl of rice and some instant coffee packets. She scooped a spoonful of rice into my open bowl, along with the coffee, as the man clasped his hands in devotion. An intense feeling of relief and gratitude arose in my chest, as the fruit of this small practice of humility and interdependence. I let the feeling wash over me as I continued on the path, with villagers seemingly surprised to see a lone monk, and even more so that I was a foreigner. The generosity and reverence shown by all the people that stopped me on my way were nothing short of unreal. As they deposited food, I would silently recite a simple wish: “May you be well, happy, and peaceful.” With a renewed faith in the process, I eventually finished the morning with a full bowl, and full heart.

As time went on, I repeated this process every day, growing stronger in my trust and confidence little by little. It was relatively common to encounter a layperson offering money in lieu of or in addition to basic food – to be fair, there is an element of convenience afforded to both sides in such cases. In modern times, division of labour and specialization allows for better efficiency and thus lower costs, and the layperson can focus on their craft or trade, rather than cooking, for example. Industrialization lead to the engagement of women in the workforce, further increasing the labor supply, as less time was needed for homemaking. There is an economic argument here, but there are certainly two sides to every coin. Just as grandma’s cooking tastes different from what is served at a restaurant, I sensed there was a deeper level of connection afforded to a donation of actual food.

When I encountered a layperson offering money, I made an exception to the solemnity of the alms round. They would generally hold the money in front of my bowl, expecting me to bless and take it. I would raise my hand in a stop gesture and recite some broken Burmese to explain myself: ငါပိုက်ဆံမရှိဘူး (pronounced ngar pitesan mashibhuu = I don’t use/have/spend money). This almost always resulted in an awe-struck response: it was apparently very uncommon for monks to uphold the discipline of not using money in Myanmar. Often, the layperson would motion for me to stay put while they ran to the nearest corner store to buy a snack or morsel of food. Ultimately, the rule did not negatively affect either side of the donor-recipient relationship, and I was frequently overwhelmed with gratitude and humility at the generosity and respect shown towards me.

I’ll endeavour to continue fleshing out this story, but I’ll stop here for now, embracing the philosophy of “done is better than perfect”. If you’ve made it this far, thank you for reading, and perhaps write a comment if you found value and would like to hear more. There are still several months in that world to recap.

Leave a Reply